While current sustainable food system initiatives in Northland are admirable, as yet, they remain relatively poorly connected. If this were to continue, such initiatives will remain as a counter-culture in the prevailing industrial food system. Local Food Northland believe that developing a Northland food policy council, founded democratically as a “grass-roots” initiative with the task of preparing a regional food plan and fostering greater connectivity is a desirable step toward a more sustainable food system.

Here is an extract about food policy councils from our current research.

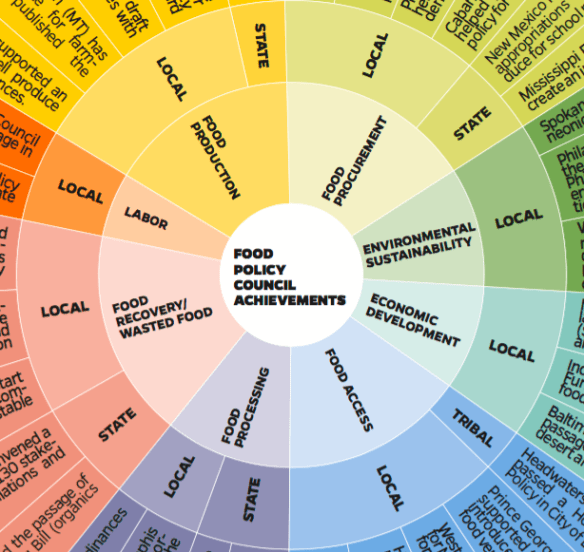

It is not surprising that we find strong momentum towards establishing sustainable food systems in the nation that has been at the forefront of the proliferation of fast food chains, food processing and long food chains. In 2015, The United States had 215 Food Policy Councils, with a total of 282 in North America.

Food Policy Councils in North America

This graph (from John Hopkins Center for a Livable Future) reveals dramatic growth in Councils from 2000 to 2015. Growth appears to have plateaued, but based on its proliferation in North America is primed to expand in other locations world-wide.

Seventy eight percent of these councils are either independent grass-roots organisations or NGOs with Twenty one percent embedded in government or government funded organisations (Center for a Livable Future, 2015).

The Center for a Livable Future’s mission is “to promote research and to develop and communicate information about the complex interrelationships among diet, food production, environment, and human health” (Center for a Livable Future, 2016). The top priorities for Food Policy Councils are healthy food access, urban agriculture/food production, education, purchasing and procurements, networking and food hubs. Other interests are anti-hunger, food waste and fitness(Center for a Livable Future, 2015).

Two examples of Food Policy Councils follow – the first metropolitan and the second regional.

The Toronto Food Policy Council (TFPC)

The Toronto Food Policy Council, established in 1991 is one of the oldest. The TFPC “connects diverse people from the food, farming and community sector to develop innovative policies and projects that support a health-focused food system, and provides a forum for action across the food system” (Toronto Food Policy Council, 2016).

Key documents include the Toronto Food Charter and Cultivating Food Connections, Toronto Food Strategy. The TFPC also collaborates with other organisations in Ontario to promote policy and legislation to shape a sustainable food system. Wayne Roberts (2014) uses a flywheel as a metaphor for food policy councils. They institutionalise and foster innovation providing momentum, rather than having new projects have to start unaided and poorly connected to the diversity in the food system.

Puget Sound Regional Food Policy Council (PSRFPC)

The PSRFPC is much younger, established in 2010. Its vision is a “thriving, inclusive and just local and regional food system that enhances the health of: people, diverse communities, economies, and environments”(Puget Sound Regional Food Policy Council, 2011). In addition to policy work, the PSRFPC has worked on farmers market viability.