Professor Barbara Burlingame provided a compelling case study about the nutrient content of local bananas at our February conference. Before returning to New Zealand she spent 16 years with the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation including the last four as Deputy Director of the Nutrition Division as was closely involved with the research referred to here.

Professor Burlingame related the story of Pohnpei, a Micronesian Island north of the equator. Over time the people their drifted away from their indigenous diet to consuming increasing quantities of imported food. There were consequences.

The change in food habits from fresh traditional foods to processed imported foods has been accompanied by high prevalence of overweight, obesity, diabetes, heart disease and cancer among the adult population, while micronutrient deficiencies, such as of vitamin A, are prevalent among children[1].

Well intentioned interventions

Starting in the 1960s, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) initiated supplementary feeding programmes to Pohnpei, using surplus commodities such as rice and tinned foods. These food aid programmes, including a school lunch programme, “introduced rice and processed foods to many children and adults in Pohnpei, establishing new food habits, attitudes and food tastes that persist today”[2].

In a story similar to that of other indigenous communities transitioning from the food systems they controlled to Western diets, the unintended consequences, especially the vitamin A deficiency, sparked further inteventions. Vitamin A supplements, including injections, were provided for children.

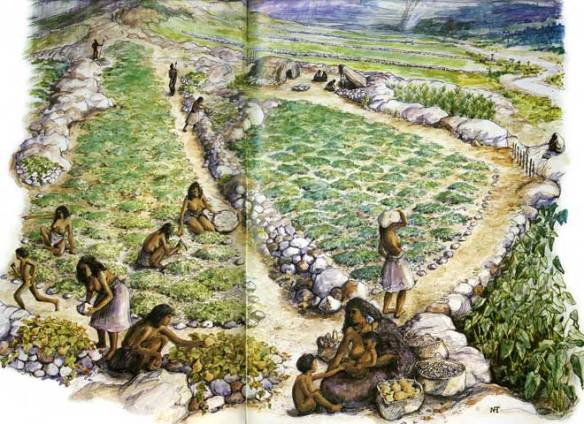

The Karat banana, often the first sold food for Pohnpei’s babies. (Photo from Web Ecoist)

Researchers, led by the late Dr Lois Englberger, turned their attention to local foods. Pohnpei has 26 banana cultivars. One of these, Karat, has deep yellow/orange flesh indicating the presence of provitamin A carotenoids.

When analysed for its nutrient profile, the Karat cultivar provided up to 2230 units of carotenes. Another cultivar, Utin Lap has up to 8508 units of carotenes. By contrast, Cavendish, the variety found in supermarkets around the world has less than five units of carotenes. The answer to the debilitating vitamin A deficiency was close by all that time. Consequently the government of the Federated States of Micronesia championed the local food movement and when Dr Englberger died in 2011, they held a memorial service in her honour.

Nutrition of Northland bananas

The health of our food can be evaluated by the nutrients it provides and the impact of artificial chemicals used in its growing, processing, transportation and storage and impacted by the way we cook it.

This website provides detailed coverage of bananas’ food value.

Fruits and vegetables with orange or red flesh are rich in carotenes, so we can anticipate that our locally grown bananas will be closer to the levels found in Cavendish bananas. However, it will be interesting to have the analysis done. Perhaps we could crowdsource funding for this to support the development of the local banana industry.

[1] Let’s go local! Pohnpei promotes local food production and nutrition for health in Indigenous people’s food systems & well-being (2013) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, page 195). http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3144e/i3144e00.htm

[2] ibid, page 194

The Drawdown project has raised my optimism about climate change. There are plenty of doomsayers who think that we are stuffed. For a whole lot of people, its a problem that is just too big to handle, so the strategy is to ignore it. In New Zealand our government tells us that we are too small to make much impact and they appear to believe, action on climate change and improving the economy are mutually exclusive.

The Drawdown project has raised my optimism about climate change. There are plenty of doomsayers who think that we are stuffed. For a whole lot of people, its a problem that is just too big to handle, so the strategy is to ignore it. In New Zealand our government tells us that we are too small to make much impact and they appear to believe, action on climate change and improving the economy are mutually exclusive.

I’ve read all the modern whole food books on the trendy bookstore shelves at the moment and I LOVE what’s happening. I love that our attitudes towards food are changing and that we are beginning to understand the true meaning of nourishment. We know now that how we source food is the first and arguably the most important step in the process. Food should be nutrient dense but it should also have a pristine conscience and be laden with good karma.

I’ve read all the modern whole food books on the trendy bookstore shelves at the moment and I LOVE what’s happening. I love that our attitudes towards food are changing and that we are beginning to understand the true meaning of nourishment. We know now that how we source food is the first and arguably the most important step in the process. Food should be nutrient dense but it should also have a pristine conscience and be laden with good karma. The absence of illness or mediocre wellness is not enough, we must be humming at exactly the right frequency so that we can connect with our whole minds to the truth of our existence. To be distracted by disease, inflammation, fatigue or pain takes us away from the core business of life – to learn and contribute.

The absence of illness or mediocre wellness is not enough, we must be humming at exactly the right frequency so that we can connect with our whole minds to the truth of our existence. To be distracted by disease, inflammation, fatigue or pain takes us away from the core business of life – to learn and contribute.