On 8 April Tropical Fruit Growers New Zealand had their inaugural public meeting at Northland Inc’s Orchard. Attendance exceeded expectations and now the TFGNZ has over 100 members. Here is Hugh’s report from the meeting. Some images are added from the TFGNZ Facebook page.

What a meeting! Thank you everybody for your support and TFGNZ is all go.

TFGNZ is the result of a group of people – all passionate about what they are growing – getting together, discussing, sharing and comparing what they are doing and what is possible.

The TFGNZ committee – from the foreground in the left, Cameron Smith, Owen Schafli, Hugh Rose, Brent Burge, David Colley and Matt Stanley

The most important asset of TFGNZ is our Members. With that in mind I would like to set out the immediate agenda as I see it and welcome suggestions to take to the next committee meeting.

The commercial growing of bananas in Northland is not a new idea but for one reason or another it has never gotten off the ground. With the downturn in the dairy economy the time is right for this to happen and I intend over the winter months get TFGNZ in front of the dairy industry so we are seen as the authority for expanding the planting of banana crops to supplement incomes and provide inexpensive feed for animals. This is a win-win situation all round as bananas quickly convert effluent into biomass and clean-up waterways.

We need to complete the incorporated society process, Once this is done we can apply for funding for funding into research as to the nutritional benefits of banana plants for cattle feed and the nutrient levels of the locally grown fruit compared to imported fruit. As I understand it we will be able to receive funding for this research from M.P.I and other agencies.

Please, if you have any bananas growing that you are able to add to the crop register please let us know or contact Matt Stanley matt@maplekiwi.com who is compiling a database of source materials.

TFGNZ will introduce its own system to identify commercially grown produce and certify organic status or otherwise.

October onwards is the planting out season for bananas so in September land needs to be cleared and stems harvested. We will coordinate teams for this purpose as required. We will be able to get existing work crews to head out and collect the stems and plant them on a grand scale by working in with the various existing agencies as each hectare of land will require over 1000 plants.

These plants are anticipated to be sold at around $10 each with a minimum of $1 per stem going to fund TFGNZ so any donated stems will help operational costs in the early stages. Organising new plantings advising on existing plantation will greatly increase the TFGNZ profile.

With commercial plantings they will initially be done with donated and low cost stems, different varieties going into each plantation. These initial stems will be monitored and those that produce the best results at each location will be cloned using tissue culture techniques to fast track the establishment of viable orchards.

As fruit comes into production then the distribution process will coordinate the flow of fruit so it reaches the consumer in optimum condition and those requirement figures are staggering!

Population of Northland is 171,400. At 18Kg per person per year, that makes 3085 tons consumed annually.

Population of NZ is 4,781,000. At 18Kg per person, that makes 86,000 tons.

At $2 per kg that’s 172 million dollars with which to create employment and industry for Northland and who knows in time there may even be some to export!

A small percentage of this will fund TFGNZ

Recruitment within TFGNZ is the first place to start, if you are skilled or able and if TFGNZ is seeking to achieve anything that you may be capable of doing then there is no reason provided you can do it you should not get the job. As each step is taken we will tell members what we are doing and where we are at. Please let us know if you can help achieve our gaols in any way and if you are prepared to serve on the committee

It’s not all about bananas!

Field trips are to be organised and other activities if anyone wishes to help in this area please let us know don’t be shy, if you have any skills you think may be useful same applies. This is a voluntary role however expenses will be met.

Owen’s pineapples sheltered by sugar cane – there are also coffee trees growing in the background

Lastly my bombshell for those who know me – you heard it here first!

Rukuwai Farm is about to go on the market! Yes up for sale and why, you may ask? Six months ago we applied to WDC to subdivide so we could sell off our house and rebuild down where I do all the growing, plantation/market garden and create a water garden to display Pauline’s Lotus plants. Sadly six months on owing to the constraints of the resource management act nothing has progressed other than the depletion of our reserves as yet another report is required. Please do not think I am having a go at WDC far from it, simply it is the framework they are obliged to work within under the resource management act however when you are 65 years of age and have still got lots to do six months is far too long for us! So we have made an offer on another property which if accepted will see us relocating – not far but it will be to a place that needs some TLC and meets our criteria for water gardens and tropical fruit.

Of course if you know anyone who wants a production platform mostly flat river silt around 100 acres with proven horticultural returns, a nice new modest home, heaps of plantings and a developing banana plantation give me a call.

We are heading into the long weekends so please, take care everybody, enjoy the break and after the committee meeting and debrief on the 18th our very first newsletter will be issued!

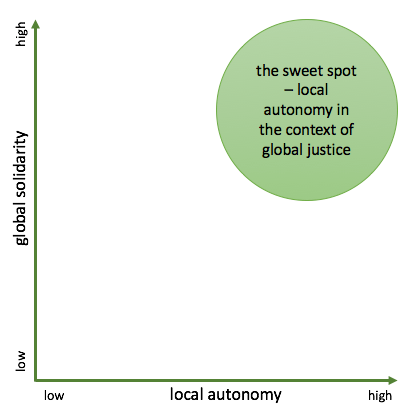

On the cusp of establishing a Northland Food Policy Council (or whatever we might call it) I have stumbled across a book that has thrown a lot of light on the policy universe. In How Change Happens, Duncan Green shares his knowledge as a long-time advocate for change. The book is available for sale, but is also

On the cusp of establishing a Northland Food Policy Council (or whatever we might call it) I have stumbled across a book that has thrown a lot of light on the policy universe. In How Change Happens, Duncan Green shares his knowledge as a long-time advocate for change. The book is available for sale, but is also  In the context of food, ideally families will have choice to eat food that nourishes without their perception being clouded by commercial considerations – especially the rapacious food and medical corporations that privilege profit over health and well-being.

In the context of food, ideally families will have choice to eat food that nourishes without their perception being clouded by commercial considerations – especially the rapacious food and medical corporations that privilege profit over health and well-being.

By Anne Palmer

By Anne Palmer